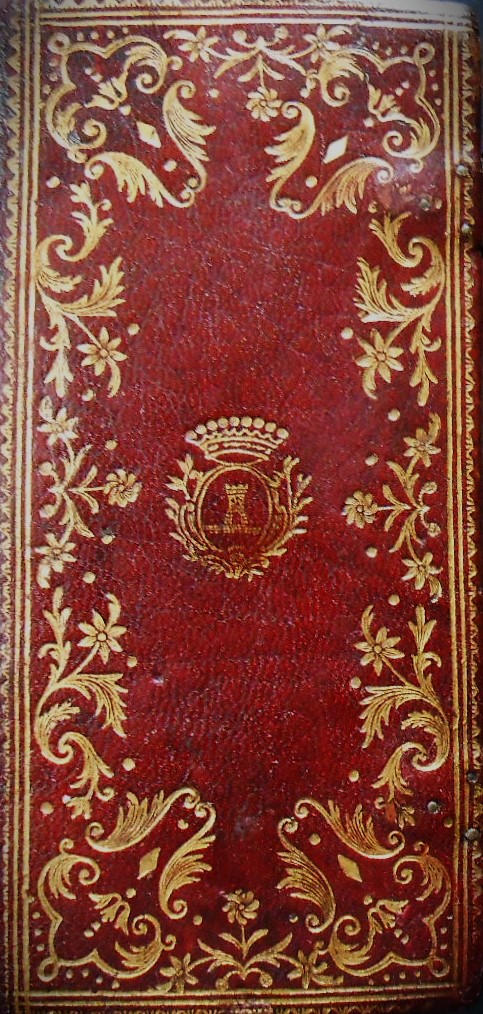

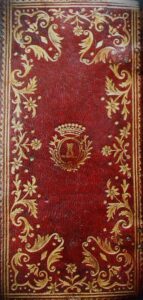

[Elisabeth-Claire Leduc]. [Prayer book]. No place [Paris ?], march 1792. Notebook. In-32. 170 pp., autograph manuscript in a beautiful handwriting in brown ink, framed by a border in brown ink. Contemporary red morocco, plain spine, lace decorated covers with gilt coat of arms in the centre, gilt roulette on the cuts and inner, silver clasps.

The autograph prayer book of Mademoiselle Leduc, Marquise de Tourvoie (1721 – circa 1793), dancer at the Opéra, daughter of a Swiss of the Palais du Luxembourg, the mistress and then the wife of Louis de Bourbon-Condé, Count of Clermont, Prince of the Blood, Abbot of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Bois, great-grandson of the Grand Condé and grandson of Louis XIV and La Montespan.

The daughter of a Swiss from the Luxembourg Porte d’Enfer, Élisabeth Leduc began her career as a gallant. After a long wait, she left the President de Rieux to follow the Count de Clermont, in 1741, urged on, it is said, by the Count’s former mistress, Marie-Anne de Camargo, who could no longer bear the state of slavery in which she found herself. The Count and Mlle Leduc both lived at the Château de Berny in Fresnes, the country residence of the abbots of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and entered into a secret marriage in 1765. They had two unmarried children, Abbé Leduc (1766-1800), who bore the title of Abbé de Vendôme, and a daughter (born in 1768). The Count of Clermont bought the seigneury of Tourvoie in Fresnes, near the Berny estate, for Mlle Leduc. The castles of Tourvoie and Berny were linked by an underground gallery. Mlle Leduc was as fickle as her lover, but he was fiercely jealous. One day, more angry than usual, he scratched her forehead with a penknife. Ashamed and repentant, he asked the king to make her Marquise (de Tourvoie) to make amends. “Bibliophily, writes Guigard, was part of social life in the eighteenth century. The great ladies in particular would have felt they were failing in all their duties if they had not been able to display, in a richly decorated salon, books with the marvellous tools of Derome or Pasdeloup. Although she was raised in the limelight, Mlle Le Duc also wanted to have a bibliographic collection which, through the splendour of its bindings, could rival those of her noble contemporaries“. Our notebook, with her canting arms, can be related to the one reproduced by Guigard, “of rare beauty. Indeed, here, the border unfolds harmoniously and delicately under the gentle firmness of its movements.” The ornate richness of the plates, hidden in her library between two copies, contrasts with the sobriety of the spine, visible on the shelves, and the humility advocated in the collection of prayers in French and Latin, among the Ave Maria and the Pater Noster. In the twilight of her life, Miss Leduc invokes the protection of “the great Saints whose name I have the honour of bearing, St Elizabeth and St Clare, my patron saints” (p 39), and prays to God for herself, but also “for the Pope [burnt in effigy in the Palais-Royal on 3 May 1791], for our archbishop, for our parish priest, for all the clergy [The Civil Constitution of the Clergy had been passed in 1790 by the Constituent Assembly], for the King and the whole Royal family, for all the magistrates [Decree on the new judicial order of 6 March 1791], for my children, for my nephew” (p 19).

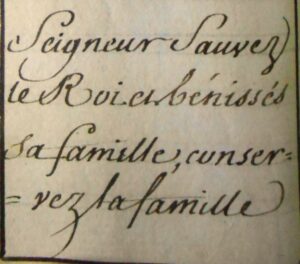

Probably written as the revolutionary turmoil progressed, she repeats her prayer, probably after the escape to Varennes in June 1791: “Lord save the King and bless his family, preserve the family of St Louis and make his children imitators of his faith“. (p. 106). Furthermore, she entrusts her moments of weakness to God: “If you do not support me with strength, I give myself over to all my resentments & I give myself over to my bad temper, to pitiful indecencies, to disgusts that bring me down, that poison everything that distresses me“.(pp. 130-131).

Shortly before the Count’s death in 1771, fearing that she would be harassed by his legitimate heirs and creditors, she sold her Tourvoie estate while retaining the title and bought a house on rue Popincourt, opposite the former monastery of the Annonciades nuns, where she died.

Guigard, Nouvel Armorial du bibliophile, 1890, t. I, pp. 174-175 ; O ; H. R., Manuel de l’amateur de reliures armoriées françaises, pl. 2374.

A few stains, originally a small hole on p. 155, not serious. Few quires offbeat, a few discreet restorations to the binding.

Rare document. Precious and moving provenance.

4 800 €