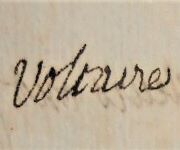

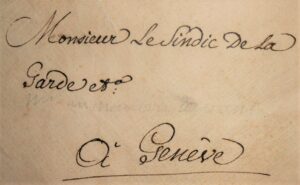

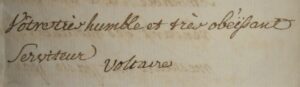

Voltaire (1694-1778). Letter signed ‘Voltaire’, Château de Ferney, 29 January 1765, to ‘Monsieur’ [André Gallatin le jeune, syndic of Genève]. 2 pp. in-4°. With its envelope written in the same hand: ‘A Monsieur / Monsieur le Sindic De La / Garde etc / A Genève’, and, on the back, the rare red wax seal with Voltaire’s coat of arms, azure with 3 golden flames.

An exceptional letter, as far as we know unpublished, in which the philosopher fears for his property at Délices and Ferney, ironises against Rousseau and mobilises himself at the head of a militia that he forms for the occasion, despite his seventy years of age and his lack of courage. All in his inimitable style, light, brilliant and occasionally caustic.

The addressee of the letter, André Gallatin (1700-1773), was a citizen of Geneva (1725-1773), a member of the Conseil des Deux-Cents (1728-1748), auditor of the Geneva courts (1733), sautier of Geneva (47th, 1743-1747), councillor of the Petit Conseil (1748-1773), syndic of Geneva (1753, 1757, 1761, 1765, 1766, 1767), and first syndic of Geneva (1771).

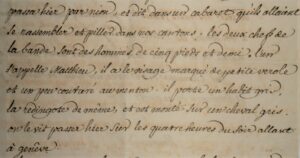

The Bailiff of Nyon and the Mayor of Gex, Louis-Gaspard Fabry, will no doubt have given his correspondent their advice « qu’une bande de vagabonds passa hier par nion, et dit dans un cabaret qu’ils allaient se rassembler et piller dans nos cantons ». [that a band of vagabonds passed through nion yesterday, and said in a cabaret that they were going to gather and pillage in our cantons.]

Voltaire gives a fairly accurate description of two of them, Matthieu and Lamain, and then blames Rousseau for the exactions of these villains.

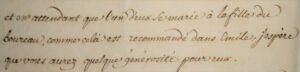

« Apparemment que ces messieurs ont passé par moutiers travers où ils ont apris que tous les hommes sont égaux, et tous les biens communs, et en attendant que l’un d’eux se marie à la fille du boureau, comme cela est recommandé dans Emile, j’espère que vous aurez quelque générosité pour eux. » [Apparently these gentlemen have passed through moutiers travers (the village of Môtiers in the Val-de-Travers where Rousseau lived from 1762), where they learned that all men are equal, and all goods are common, and while waiting for one of them to marry the daughter of the butcher, as recommended in Emile, I hope that you will be generous to them]. He patrolled his house and those of his neighbours last night.

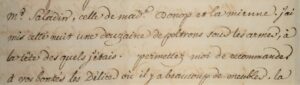

« J’ai mis cette nuit une douzaine de poltrons sous les armes, à la tête desquels j’étais. » [Last night I put a dozen cowards under arms, led by myself.] [See the description of his small troop in the letter of the 28th to Fabry (letter no. 8688).] And he is worried about his home in Les Délices: « Permettez-moi de recommander à vos bontés les Délices où il y a beaucoup de meubles » [Allow me to recommend to your kindness Les Délices, where there is a lot of furniture] as well as that of his neighbour Pictet. And, before signing, he concludes with a great deal of humour:

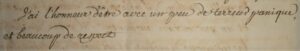

« J’ai l’honneur d’être avec un peu de terreur panique et beaucoup de respect » [I have the honour of being, with a little panic terror and a lot of respect]

In a letter dated the same day, Voltaire informed Louis-Gaspard Fabry that a troop of smugglers on horseback was passing through, and that ‘he has written to the syndic of the Geneva guard accordingly’. (Correspondance, Bibl. de la Pléiade, letter no. 8693), and he wrote again that evening that it was eighty smugglers led by the sister of Mandrin, the famous smuggler executed in Valence in 1755 (letter no. 8694). This concern can be explained by the minutes of the Consistoire de Genève dated 30 January: ‘We read a letter from the seig[neu]r bailli of Nyon dated 29 January […] about a meeting that some villains had arranged in Nyon to go from there to plunder a castle in France, who, having gone to Nyon, took the road to Joigne and Pontarlier, of which the said sei[gneu]r bailli gave notice to Gex, Saint-Claude and Pontarlier’. Voltaire was concerned not only for his château at Ferney, where he lived, but also for his residence at Les Délices, near Geneva, which he was about to sell to the banker Jean-Robert Tronchin.

Voltaire poked fun at the ideas developed by Rousseau in his two famous works published in 1762: he criticised Le Contrat social (The Social Contract) for its emphasis on Equality and the notion of the Common Good, and mocked Émile for its considerations on marriage in Book V, referring to a passage in which the philosopher from Val-de-Travers got a little carried away : « Voulez-vous prévenir les abus et faire d’heureux mariages ? Etouffez les préjugés, oubliez les institutions humaines et consultez la nature. […] l’influence des rapports naturels l’emporte tellement sur la leur [celle des rapports conventionnels] que c’est elle seule qui décide du sort de la vie, et qu’il y a telle convenance de gouts, d’humeurs, de sentimens, de caractères qui devroit engager un père sage, fut-il Prince, fut-il monarque, à donner sans balancer à son fils la fille avec laquelle il auroit toutes ces convenances, fut-elle née dans une famille déshonnête, fut-elle la fille du Bourreau. » (Œuvres complètes, Bibl. de la Pléiade, tome IV, pp. 764-765).

Rousseau was finally driven out of Môtiers by its inhabitants in September 1765 and found refuge on Île Saint-Pierre on Lake Bienne.

Not in the Correspondance published in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

On the envelope, another hand has written ‘Lettre de Voltaire / 1767 [sic]’ in ancient black ink, and a line has been written in pencil.

Sold