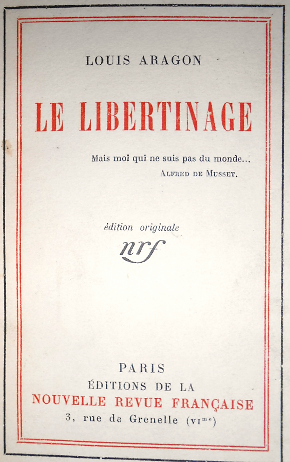

Louis Aragon. Le Libertinage. Paris, la Nouvelle Revue Française, 1924. In-8° of 254, [1] pp. Red and yellow half-chagrin with corners, flat spines, gilt title, year gilt at foot, double cold fillet on covers, plum-coloured percaline with small squares on covers, endpapers illustrated with a scattering of roses on an ivory background, gilt head, cover and back preserved (Binding of the time).

First edition, printed in an edition of 900 copies, this one no. 103 out of 750 reserved for friends of the first edition on vellum pur fil Lafuma-Navarre.

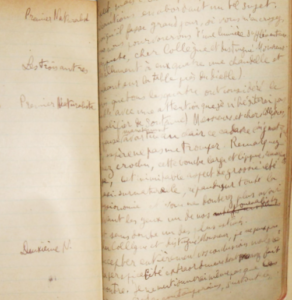

The copy is interleaved with single-sided proofs, abundantly corrected by the author, mainly concerning typography and page layout. With the wet stamps of the printer F. Paillart, Abbeville, 29, 31 January and 5 February, the final printing being dated 31 March 1924. A few reinforced leaves on the spine; the binder’s chisel has sometimes trimmed the author’s indications.

A collection of plays and stories that glorify physical love (“La femme française”) and exalt anarchy (“Lorsque tout est fini”, in which Jules Bonnot (“B.”) and his gang appeared in 1912). The “Preface” is an important document, not only in terms of our knowledge of the author at the time, but also in terms of the intellectual climate of Surrealism, of which Aragon was, in 1924, the most conscious representative along with Breton. In it, he extols love: “I think of nothing but love […] For me, there is no idea that love does not eclipse. Anything that stands in the way of love will be annihilated if it is up to me. This is what I crudely express when I claim to be an anarchist. This is what will drive me to the greatest exaltations, whenever I feel that the idea of freedom is at stake for a single moment” (p. 9). This obsession with love was to be one of the main line of his work.

In terms of language, Libertinage contains “some of the most fascinating pages the poet wrote in the first period of his literary life” (Laffont-Bompiani, Dictionnaire des œuvres, IV, 198-199).

This copy contains two unpublished autograph manuscripts, as far as we know :

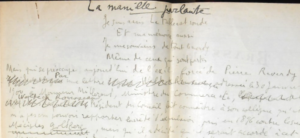

La Manille parlante. No place or date [Paris, between May and July 1922]. Autograph manuscript signed “Louis Aragon“, 2 ½ pp. on 3 filled in-4° leaves, recto only, on ruled paper with the illustrated letterhead of the Brasserie Excelsior, 81, Avenue de la Grande-Armée, Paris.

First draft manuscript, with numerous handwritten corrections, erasures and additions.

Short text written in support of the anarchist Mécislas Charrier (1895-1922), son of the Polish-born anarchist poet and writer Mécislas Golberg (1869-1907). Although he had no direct blood on his hands, Charrier was sentenced to death and executed on 2 August 1922 for his part in the attack on the Paris-Marseille train, in which a young man who had tried to resist was killed; an inspector was also killed during the arrest of his accomplices, who were shot dead. In the courtyard of the Santé prison, the condemned man walked to the guillotine singing L’Internationale, Gloire au 17e and La Carmagnole. He was the last anarchist to be executed in France.

Probably intended for a newspaper, Aragon wrote this article at a Parisian brasserie table. After using 4 lines from Tard dans la nuit, a poem by Pierre Reverdy, as a tribute to his friend (“But who cares today about Pierre Reverdy’s forced exile?“): “I’m sitting down The table is round / And so is my memory / I remember everyone / Even those who have left“, Aragon draws a parallel between the fate of Mécislas Golberg and that of his son, who was to be sent to the scaffold. He speaks uncompromisingly of the libertarian poet, “an incredible heap of disconcerting truisms, a literary slacker, a pedlar’s thinker, whose attitude, beyond his natural stupidity, now seems the only one truly sympathetic and worthy of encouragement. For him, the ideas of Socrates owe their fortune only to the suicide of this theorist“; and Aragon castigates an opportunist publisher, “and now it’s the murder of the train 5 that gives a publisher the idea of reprinting Mécislas. They will be robbed, the curious of my acquaintance, who rushed to the Letters to Alexis in the hope of obtaining cheaply, in the shadow of the guillotine, the thrill of the little death. Golberg’s masterpiece is really called Mécislas Charrier, and it was to him, without knowing him, that the Friends of Golberg, under the presidency of Paul Adam, paid tribute by publishing the fragments of Social Institutions.

There are strange inheritances: they now find it natural that those who indiscriminately turned father or son into a criminal or a genius should receive a death sentence for any soup Charrier makes by way of copyright. “Let us turn away,” wrote his mother, “from the tomb in Fontainebleau” [where Golberg is buried]. It was on this tomb, however, and not on the one about to be built, that the speeches were made. The knife was reserved for the only man who could say out loud, without arousing hilarity: ‘I don’t give a damn about my interests’.” He denounced the baseness of the people and the hints of anti-Semitism, xenophobia and anti-anarchism: “Now listen to the people in the underground trains and cafés. This is a great opportunity to blame Jews, Russians, anarchists and intellectuals for anything. Nobody misses out. And it’s not the inadequacy of his thought, not the vulgarity of his rhetoric, that today allows the first person to do his business in five seconds with the colossus of a baudruche who imposed himself on Mirbeau“.

In fact, according to him, it was up to the son to destroy the memory of a famous father, a grating oedipal satire of recent Freudian theories: “it was up to the son to lose the memory of his father in the hearts of good people. Ah, if I’d had an illustrious father, how much fun I’d have had destroying his reputation just by spilling a little polytechnician blood under an alarm bell. It’s easy.” Then and he warns with acerbic humour the celebrities of the moment, literary, scientific and military against their offspring. “Dear Sirs, who have taken on obligations to posterity, François de Curel, Maurice Barrès, Rudyard Kipling, Gabriele d’Annunzio, for example, beware of your offspring: they could well get in your way. I’m giving my recipe free of charge to Maurice Rostand, who seems to be suffering from paternal competition: put a mask over your face and get on the fast track against the flow.

Jean-François Lacenaire, a murderer whom Laforgue cites as one of the great Romantics, between Châteaubriand and Byron, but whom Monsieur Paul Souday considers a bad poet, when asked what he would do with his freedom if he regained it, replied: I would do it again. Will Monsieur Millerand, who did not pardon Landru, do it again? I don’t know yet.” The poet goes on to imagine Foch or Albert Einstein, [who recently won the Nobel Prize], as child-murdering rapists. “In the meantime, I indulge in the pretty mental game of putting our best celebrities through the pincushion of a criminal case, and I amuse myself by wondering what would become of Marshal Foch or Einstein if one or other of these two international glories suddenly started doing his little Soleilland.” [Albert Soleilland (1881 – in prison in 1920) was convicted of the rape and murder of an eleven-year-old girl in 1907]. Aragon concludes with scathingly ironic attacks on three writers he considers mediocre: “After all, my friends, it is never too late to do well: Monsieur René Bazin can still, like the Marquis de Sade, attach his name to a vice, Monsieur Fernand Vandérem can acquire a critical sense, and Monsieur Binet-Valmer can one day pass for a talented writer.”

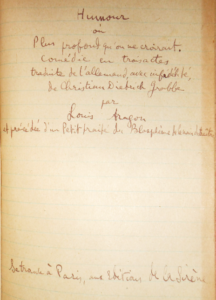

Humour, ou Plus profond qu’on ne croirait. Comédie en trois actes traduite de l’allemand, avec infidélité, de Christian Dietrich Grabbe par Louis Aragon et précédé d’un Petit traité du Blasphème de la main du traître [sic]. Se trouve à Paris, aux Editions de la Sirène. No place or date [ca. 1923]. Autograph manuscript notebook in black ink, (18.8 x 11 cm), of [21] lined ff., text on recto with facing didascalia written on verso, red edges.

Translation of Scherz, Satire, Ironie und tiefer Bedeutung, written by Gabbe in 1822 and published in 1827 (Dramatische Dichtungen, Frankfürt, J.C. Hermann, 1827). André Breton described it as “a work whose genial buffoonery has never been surpassed“. The play was translated by Alfred Jarry and partially published in 1900 in the Revue Blanche under the title Les Silènes, then by Aragon in Paris-Journal at the end of April 1923. Grabbe’s theatre was rescued from oblivion by the Surrealists, and our manuscript fits in perfectly with this approach. The place of publication announced by Aragon, the “Editions de la Sirène“, could this be a nod to Jarry’s Silènes, as well as a reference to the avant-garde publishing house Sirène founded by Paul Laffitte in Paris in 1917, which launched promising young authors?

The poet’s translation, crossed out and corrected, stops halfway through Act I, Scene 3, corresponding to pp. 53 to 82 of the 1827 German edition, and its translation differs from that proposed by Jarry. Did Aragon intend to translate Grabbe’s play only to decide to publish Jarry’s partial translation in Paris-Journal, which he was directing at the time? This would seem to be an interesting aborted publishing project. Our manuscript differs considerably from the text entitled “Les Silènes” published in the chapter entitled “Christian Dietrich Grabbe” in André Breton’s Anthologie de l’humour noir, Œuvres complètes, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, tome II, pp. 929-936.

The play will be published in 1971, translated by Henri-Alexis Baatsch, under the title Plaisanterie, Satire, Ironie et Sens plus profond, by Éric Losfeld, Ludd.

The promised Little Treatise on Blasphemy is not included. Another project with no future?

An exceptional copy.

7 500 €