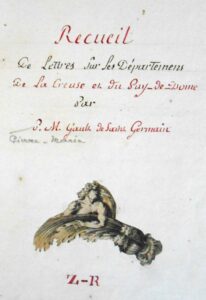

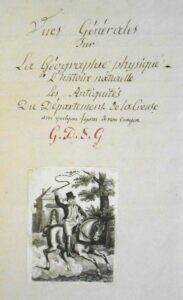

Pierre-Marie GAULT DE SAINT-GERMAIN (1757-1848). Recueil de Lettres sur les Départemens de la Creuse et du Puy-de-Dome. Engraved frontispiece of the author, title, [3] pp. [followed by a second title:] Vues Générales sur la Géographie physique, l’histoire naturelle, les Antiquités du département de la Creuse avec quelques figures de mon crayon. Guéret, décembre 1809-juillet 1810. Autograph manuscript signed. In-4° on ruled laid paper. Title, 111 pp. 16 pp. of engravings and mounted drawings, and 1 large folding pen-and-ink map bound at the end. Contemporary green half-basane, romantic spine, red morocco title-piece.

One of the first, if not the very first, encyclopaedic works on the Creuse, this ancient province of the Marche, plunged, according to GAULT DE SAINT-GERMAIN, into apathy for centuries (p. 69).

Manuscript published in part under the title Lettres inédites sur la géographie, la physique, la topographie, l’histoire naturelle, les antiquités et les hommes illustres de la ci-devant province de Marche, écrites en 1809 et 1810 par M. Gault de Saint-Germain, peintre, published in Clermont-Ferrand by A. Veysset, in 1861, in-12, 68 pp. (Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris, cote 8-NF-71795).

Richly illustrated with fourteen drawings and one large-format autograph map, all originals by GAULT DE SAINT-GERMAIN, a portrait of the author lithographed by ROUARGUE, four pasted-on prints, and various press cuttings on weathering pasted on the first endpapers. The manuscript contains a few erasures and strikethroughs, as well as marginal annotations by the author.

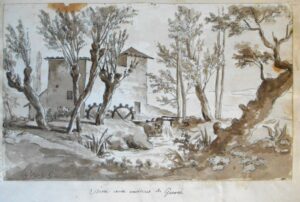

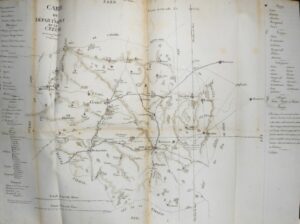

According to Camilla MURGIA, Pierre-Marie GAULT DE SAINT-GERMAIN was “a relentless researcher, a shrewd historian […] and a passionate lover of the arts”, and he pursued a career as a painter, writer and teacher. A pupil of DURAMEAU, Louis XVI bought Vue du Port et de la rade de Moka in 1789, and from 1791 to 1801, “he exhibited some good landscapes at the Salon” (Bénézit); he published a fairly large number of writings on drawing and engraving, gave articles to the Journal des Beaux-Arts and to many periodicals, while writing a Vie et Œuvres de Nicolas Poussin and publishing a new edition of the Lettres de Madame de Sévigné ; finally, having fled Paris under the Terror to take refuge in Clermont-Ferrand, he taught drawing at the École Centrale from 1792 to 1794, was curator of historical monuments in the Puy-de-Dôme department from 1794 to 1796, and after returning to Paris in 1797, left to teach drawing in Guéret from 1809 to 1810, during which time he wrote our manuscript, an exhaustive description of the Creuse, in the highly fashionable epistolary form of the Encyclopédie. These lively, erudite letters to Madame xxx [Madame BEAULATON, whose pastel portrait he painted around 1792, wife of a judge who was a member of the Clermont-Ferrand Academy] are interesting reads, illustrated with engravings and delicate washes that the author had carefully made in his notebook during his travels (Guéret, Jouillat, Aubusson, Bourganeuf, Châteauneuf, flacons, spoons, costumes, landscapes and genre scenes, Châteauneuf, flasks, spoons, costumes, landscapes and genre scenes). The book ends with a magnificent fold-out map of the Creuse region that he drew in pen and wash, meticulously depicting ancient towns, burial sites, castles, monasteries, abbeys and priories, as well as Roman roads and mineralogical resources, with a list and location of courts, prisons, hospices, police stations, colleges and bridges in the margins.

Our manuscript is the one referred to by G. Grange in his introductory note to the 1861 edition of Lettres inédites sur la géographie, la physique, la topographie, l’histoire naturelle, les antiquités et les hommes illustres de la ci-devant province de Marche, écrites en 1809 et 1810 de 1861. “In a first volume written on the Auvergne, […], this author announced, as a supplement to his work, a second part dealing with the history of the Marche, with some drawings made by him from life. Whatever research we have carried out to date, we have been unable to discover this manuscript. It is therefore in order to preserve this curious document for amateurs (whose plates we deeply regret) that we are publishing what remains of it.“

In fact, only letters II and III (pp. 9 to 21) of our manuscript are edited (pp. 6 to 35), without many of the notes in the manuscript, and with a few paragraphs removed (pp. 32 and 33 of the ms) or added (pp. 34 and 35 of the printed version). In addition, the 1st letter of the printed version, dated 18 November 1809, does not appear in the manuscript; it cites elements and details such as inns, factories, dialects, the “Devil’s Bridge” and costumes, borrowed from pp. 55 to 58 of the manuscript. Of course, the original drawings have not been published.

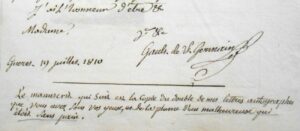

The 1st letter, unpaginated, sent from Guéret on 19 July 1810, serves as an introduction: “The manuscript that follows is a copy of the double of my autograph letters that you have before you, and from the pen of an unfortunate man who was without bread”. Despite the political obscurity of the department, the sadness and monotony of its unattractive mountains and its lack of historical interest, the Creuse “has its territorial riches like any other; it [the department] has its mountains, its quarries, its mines, its pastures, its livestock; it has its plants, its ponds, its rivers, its fish, its animals, its birds, its particular insects; it also has its remarkable subjects – in the obituaries of the natives. Its population is considerable for the size of its territory. The inhabitants are inclined towards trade and agriculture, and all they need is a perfect knowledge of the soil they cultivate to overcome the obstacles and seize the advantages.” He therefore hopes “that you will give a favourable reception to the views and ideas that I have hazarded on one of the regions of France that has perhaps been the most ignored until now”.

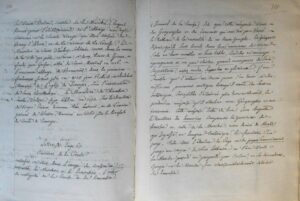

The pagination has probably been revised by the author, the previous one crossed out, before entrusting his manuscript to the bookbinder, whose knife has trimmed some of these new paginations. The manuscript text has been reduced from 160 to 104 pages, to which the author has added notes and illustrations. The continuity of the manuscript is not affected, although the letters V to VII indicated in the Table have been removed; they dealt with zoology, agriculture, rural economy and animal husbandry (Letter V), ornithology in general and that of the Creuse in particular (Letter VI), and finally the reptiles, fish, insects and watercourses of the department (Letter VII).

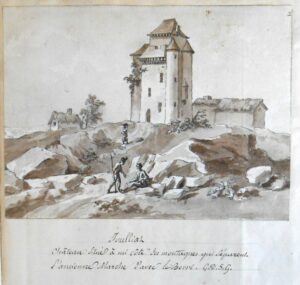

I. Route de la Sablière de Guéret à la Châtre, nature of the soil, geology; Joulliat monument [for Jouillat], with drawing of the château p. 114; the ploughs, the unhealthy climate and the vitiated nature of the air causing many diseases; sad and uniform vegetation; beautiful view of the Saint-Vaulry mountains.

II. Poor quality of the topsoil, (“the soil, the plants, the people, the animals, in a word even country life, everything lacks colour, phisionomy and character“), meteorological observations on Guéret and its surroundings, its topographical situation ; effects of the watery meteors on the mountains, their influence on the inhabitants who are “of a mediocre stature, they have narrow shoulders, hocks bending under the knee and tire easily under the weight of work; this degenerate constitution is remarkable in the conscripts; although young, they are gaunt, a little stooped and without ardour; rarely do they produce handsome men for the armies. “ Observations by CASSINI and M. de LAMBRE on the Sermur tower, curious phenomena on air currents (from the faubourg de l’Etang to halfway up the Bois de la Rode), with a nice digression on artistic representations of halos; finally, he mentions violent meteorological contrasts (thunderstorms, lightning, hurricanes, etc.) and meteors.

III. Ancient and modern history of the department. (He deplores the absence of a monastic library in Guéret). The oldest monuments, with their inscriptions, burials and funerary objects (La Souterraine, Ahun, La Courtine), Roman roads and Caesar’s camps, religious antiquities (Saint Pardoux monastery).

Finally, the monuments of Guéret: “Whim or need have been consulted more than art in the whole of the town of Guéret and even on its monuments which have neither appearance, nor dignity, nor taste either outside or inside. The parish church is a stone quarry, crudely decorated. The palace and the courtroom are more reminiscent of a community of merchants than the seat of justice. The public fountains resemble small sentry boxes.” He goes on to describe the château, both inside and out, then the prefecture building and the college, the Guéret hospice, which can hold 300 patients, its organisation and operation, and those of the département, and finally the prisons “which were once so unhealthy in Guéret, have been repaired, enlarged, surrounded by airy courtyards, where prisoners of both sexes can walk separately; Elsewhere, they have remained in a state of insalubrity that makes humanity shudder“, with the exception of Bourganeuf, which is more spacious and better ventilated. This is followed by a “Table of famous men from the former province of La Marche”, from the 13th century to the end of the 18th century.

IV.Excavations at Boussac (1782-1783), the ancient baths of Fades and their legend, the mineral waters of the Creuse (Evaux, with description, Blessac and Mallereix), the antiquities of Aubusson, the fortress of Crozant, Petite and Grande Creuse.

V. Only the note on p. 110 about the “Ouvriers de la Creuse” remains. He deplores the fact that the Marchois and the Limousins are confused and the unfavourable opinion that writers have expressed about them: “They are heavy in their way of life, dirty in their furniture and their tables, sordid in their households, thrifty and a little stingy, great bread eaters, superstitious, rather rough, superb and glorious“.

VIII. Mores and customs of the department. Guéret “has no shows, no public festivals, no society“, “what would I have to draw from meetings for eating, gambling and gossiping? ridicule?”. He criticised the department’s illiteracy (30 reading and writing teachers for 293 communes, with a third of the mayors unable to read); this ignorance fosters poverty, misery and kills industry. He describes a farmhouse, a model of “the vice of rural architecture“, then goes on to describe the people of Creuse: “not very courting by nature, they are generally good fathers, good husbands, but they wear an air of disdain about their behaviour in the home that seems to warn women that they are slaves. They are excessively self-interested, not very hospitable and only welcome strangers when they have something to look forward to. They are quick to decide and slow to act, very religious and often devout to the point of superstition.”

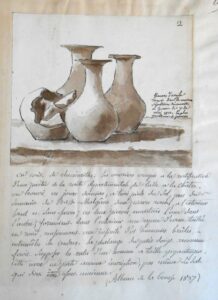

He talks about village festivals, their appetite for bread, disastrous therapeutic practices, funerals and mourning, wedding ceremonies depending on the region of the département, the “heavy and gloomy” dance, “their music is sour and monotonous […] Les bourées d’Auvergne sont méconnoissables quand les Marchois les dansent”, the costume which “is nothing remarkable” [illustrated p. 125] and the wearing of clogs. Finally, he mentions the discovery in Guéret of ancient burials containing bottles [ill. p. 119] from which he had collected balsam, and a small spoon used in ancient sacrifices [ill. p. 129].

IX. Industry, manufacturing and commerce. Aubusson [with illustrations] and its “Manufacture de Tapisserie de haute-lisse” (tapestry manufacture) in decline; he deplores the absence of a school of drawing “from which would soon emerge a nursery of workers who would restore to their manufacture the fame it has lost“; however, he notes that taste for the art of tapestry is not being lost in Aubusson and that “emulation is being revived among its manufacturers, but they should bear in mind that in order to obtain votes and sales, they must work to place themselves in the line of progress that the arts have achieved in the last twenty years. ”

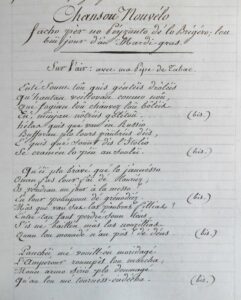

He talks about the management of the company, and the dynamism of Aubusson, which “had the good sense to build and maintain a brewery, and it is the only one; it makes around 250 sheets of beer a year“. He then turns to Bourganeuf and its paper mills, those of Felletin and Saint-Quentin, with their paper defects, and the failure of the Pont-à-la-Dauge paper mill. He notes the underdeveloped tannery; the production of knitted stockings (with a description of the workers), canvas (the department’s major production), drapery (coarse fabrics), candles (defective), pottery (Saint-Loup, coarse), millinery, glassmaking (Coupie). He then describes the fairs and markets (more than 300), and the food trade (wheat, rye, buckwheat, oats, barley, lentils, chestnuts, which people suffer greatly when they are in short supply, vegetables and fruit). He mentions beekeeping, which was poorly mastered. He then goes on to talk about communication routes, a source of industrial development (the Devil’s Bridge at Anzême), and then the dialect (with a song by FOUCAUD). Finally, he recounts a procession led by Mr DELILLE, the parish priest of Guéret, with its country feast.

X. Mineralogical production. Quality granite, widespread quartz, micaceous schist, iron deposits, millstone, rock crystals, magnesian rocks covered with a kind of lichen, sorrel (which “macerated with urine and reduced to a paste gives scarlet, violet and blue“), clay (on this subject, he deplores the use of “metallic glass to glaze pottery suitable for cooking edibles; this varnish, which is soluble in fats and acids, is infinitely dangerous“), steatite (which can replace soap). He goes on to talk about coal production, which needs to be developed: “the lack of consumption and communication is the main cause of the slowness and poor means they [the Creusois] use to exploit their mines“, the antimony mines. He then lamented the Creusois’ lack of interest in the sciences, arts and literature: “the capital city even seems to repel them. I have tried several times to inspire a taste for a literary society there, but the smallest meeting in this respect seems impossible.” Guéret does have its men of merit, and he mentions several of them (JOULIETTON, MICHELET, GRAND, DUPUIS). “There are about two printers in the department, I don’t know of a single bookseller“. Regarding vaccination, the practice is spreading with alacrity. In a postscript, he describes a new antique flask that he discovered and from which he had incense and hawthorn grains burnt to embalm his room.

XI. Vegetation, flora, trees, fruit and vegetables.

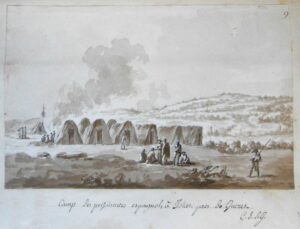

In a postscript, he describes the Spanish prison camp at Joliet near Guéret, on the road to Moulins [with illustration on p. 135]. “It is a hideous sight to see the prisoners of this nation camped under nasty huts, built especially for them and in order to protect the town from the epidemics they infect the air with wherever they go, and to stop a plague of which many people were victims before this precaution was taken. This camp, Madam, is a gathering of itinerant spectres who spread misery and death over a vast cemetery. The illuminations of the St John’s Day bonfires distract my sight from this picture that makes humanity shudder“. He deplored the fact that the festivities of St John’s Day were falling into disuse, abandoned to children “who often, unsuspectingly, preserve the most ancient customs in their games”.

On a peace of paper bound, there is a “continuation of the observation on mountains” concerning the alleged volcanoes of the Creuse, a theory refuted by Gault.

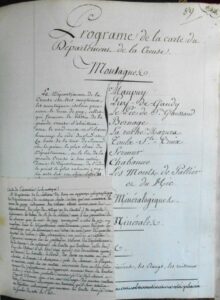

This is followed by the “Creuse Department Map Programme“, the Table and a page of omissions.

7 pp. of notes on fine paper (pp. 105 to 112) replacing revised and corrected footnotes precede the author’s drawings captioned in pen:

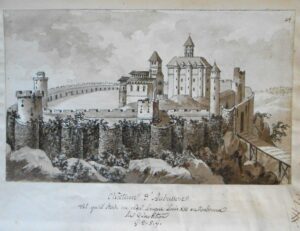

« La Ville de Guéret prise sur la route de Moulins », « Joulliat, château situé à mi côté des montagnes qui séparent l’ancienne Marche d’avec le Berry », « Château d’Aubusson tel qu’il étoit en 1646 lorsque Louis XIII en ordonna la démolition », « Flacons d’argile trouvés dans les anciennes sépultures découvertes à Guéret le 7 de mai 1810. Les plus grands ont 5 pouces », « Salle de spectacle de la ville de Guéret », [geological landscape, not captioned], « Costume des hommes de la Marche », « Château de Bourganeuf, La tour de Zizime est à gauche », « Usine aux environs de Guéret », [a spoon], « Chateauneuf sur la rivière de Cher, la ville divisée en haute et basse forme une espèce d’amphithéâtre dont le château occupe la partie supérieure. Il a été bâti par Guillaume de l’Aubespine, seigneur du lieu jadis », « Pont sur la rivière de Cher à Châteauneuf », « Etude d’après Nature près de Crosant. L’aqueduc est ajouté », « Camp des prisonniers espagnols à Joliet près de Guéret », and « Carte du département de la Creuse, dressée par l’auteur pour sa correspondance ».

Hœfer, Nouvelle Biographie générale, t. XIX, pp. 666-667 ; Bénézit, Dictionnaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, t. IV, p. 642 ; see about the author : C. Murgia, Pierre-Marie Gault de Saint-Germain (c.1752-1842): Artistic Models and Criticism in Early Nineteenth-Century in France, Oxford University, Department of Art History, 2008 (doctoral thesis), and Pierre-Marie Gault de Saint Germain (1752-1842) and the practices of collecting during the early 19th century in France publié en 2018.

Enriched with 4 signed autograph documents.

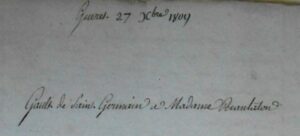

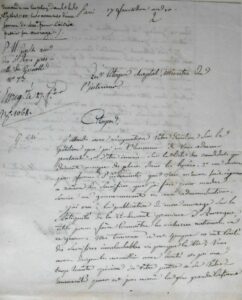

● Pierre-Marie GAULT DE SAINT GERMAIN. Autograph letter signed, Guéret, 27 décembre 1809. « a Madame Beaulaton ». 7 pp. ½ in 4°.

1st version of letter I of the manuscript, with a few variants.

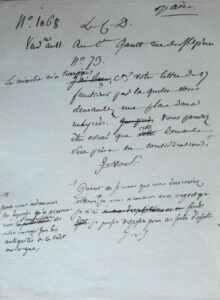

● Pierre-Marie GAULT DE SAINT GERMAIN. ALS « Gault », Paris, 17 fructidor an 10 [September 4th 1802], « au citoyen Chaptal, ministre de l’intérieur ». 2 pp. in-4°.

He asked for a job at a lycée and an advance of 400 livres to help cover the publication costs of his work Tableau de la ci-devant province d’Auvergne, published that year by Pernier.

“I await with resignation your decision […] concerning 1° my inclusion on the list of candidates for places in the lycées. 2° the help in the form of allowances that you have given me to hope for because of the sacrifices I have made to be of service to the government and administrations.

I thought the publication of my work on the Antiquities of the former province of Auvergne would be useful in making known the national riches in this area. My work at that time cost me incalculable sacrifices of almost a lifetime; you have deigned to welcome them with kindness, and I have too high an opinion of your justice and humanity not to have the greatest confidence in this omen of benevolence and in the obliging promises of interest and protection with which you have honoured me.

I am so hard-pressed at the moment to meet the expenses I have incurred printing the engravings for this work, and I have no other resource than sales to honour the commitments I have made; in this respect I am counting on your kindness to help me in this circumstance.

If you do not deem it appropriate to grant me the grace I am asking for, Citizen, advance me the sum of four hundred livres and the bookseller Pernier will pay this sum into your coffers as and when the funds come in from the sale of the work. This known benefit will help me for the moment and will pull me back from the precipice where I am ready to fall.

Give yourself, Citizen Minister, the sweet satisfaction of coming to the aid of a father of a family who has so much to merit your respect.”

●With the draft of the reply, signed J. v. S., Paris, vendémiaire an 11 [September-October 1802], to Citoyen Gault, rue des Sts Pères, n° 73. 1 p. in-8°.

His request for a place in a lycée would be considered, but to compensate him for the expenses incurred by the publication of his work, he had no funds available “for these kinds of purposes“.

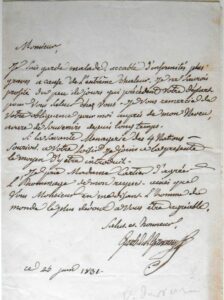

● Pierre-Marie GAULT DE SAINT GERMAIN. ALS, no place, 25 juin 1831, to « Monsieur Fournerat, substitut du Procureur du Roi, rue de Doyenné n°3 ». 1 p. in-8°, autograph address on the back.

Very tired, he did not visit her before his departure.

“I am a sick guard, burdened with more serious infirmities because of the extreme heat. I cannot take advantage of the few days before your departure to greet you at home. I thank you for your kindness on my behalf to my nephew, who has long been short of memories.

If the learned Menagerie of the 4 Nations smiles at your leisure, I enclose herewith the means of being introduced to it.

I beg Madame Cartier to accept the homage of my respect, as well as you, Sir, by telling me that I am the man of the world most devoted to pleasing you.”

Charles FOURNERAT (1780-1867), Imperial Prosecutor at Mantes-la-Jolie, was a deputy for Seine-et-Oise in 1815, during the Cent-Jours. A supporter of the Restoration, he then became a deputy royal prosecutor in Paris.

Circle on frontispiece, foxing on fold-out map; restoration on spine and corners.

4 500 €