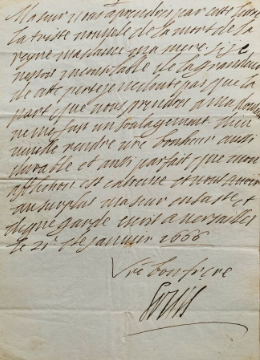

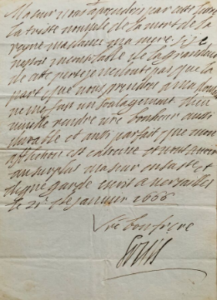

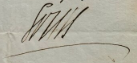

Louis XIV (1638-1715), King of France. Letter signed “Louis” (autograph signature), written by the secretary of the hand Toussaint Rose, Versailles, 21 January 1666, addressed to “ma seur“. 1 p. in-4°, very discreet mourning border.

A particularly moving letter of condolence from the King to a crowned head of state announcing the death of his mother, Queen Anne of Austria, on the previous day.

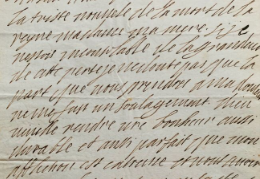

“My sister, you learn by this letter the sad news of the death of the queen madame my mother. If I were not inconsolable at the greatness of this loss, I have no doubt that the share you will take in my grief will be a relief to me. May God make your happiness as lasting and as perfect as my affliction is extreme and have you in addition my sister in his holy and dignified guard. written at versailles le 21e of january 1666

Your good brother

Louis‘.

“A son never honoured his mother more during his whole life,” wrote Charles Perrault in his Mémoires de sa vie.

On 20 January 1666, Anne of Austria died in the Louvre, aged 65, of breast cancer that had appeared two years earlier. Her suffering was increased by the doctors’ relentlessness. Overwhelmed, Louis XIV, in tears, lost consciousness. He wrote in his Memoires: “This accident, although prepared by a long-lasting illness, did not fail to affect me so noticeably that for several days I was unable to talk about any other consideration than the loss I was experiencing.

[…] The vigour with which this princess had supported my crown in the times when I could not yet act, was a mark of her affection and her virtue. And the respects I paid her on my behalf were not mere duties of propriety. The habit I had formed of living in the same house and sitting at the same table with her, the assiduity with which I saw her several times a day, was not a law I had imposed on myself for reasons of state, but a sign of the pleasure I took in her company. After all, the abandonment which she had so fully made of her sovereign authority had made it sufficiently clear to me that I had nothing to fear from her ambition not to oblige me to hold her back with affected tenderness.

Not being able after this misfortune to suffer the sight of the place where it had happened to me, I left Paris at the same hour, and I withdrew first to Versailles (as the place where I could be more in particular) […].

The letters I had to write about this accident to all the princes of Europe cost me more than one would think, and particularly those to the emperor, the kings of Spain and England, which propriety and kinship obliged me to write with my own hand. [Added in the margin of the manuscript:] “For in the first moments of a sensitive sorrow, it is difficult to force ourselves to explain it to others, without increasing it in us by the memory of some new circumstance.” (Mémoires de Louis XIV, Paris, Didier, 1860, tome I, pp. 119-123).

The monarch paid his dear mother a beautiful tribute by declaring: “She was not only a great queen, she deserves to be put in the rank of our greatest kings!

Toussaint Rose (1611 [or 1615]-1701), secretary to Cardinal de Retz and Cardinal Mazarin, was secretary to the King’s cabinet from 1657, and a member of the Académie française in 1675. He imitated Louis XIV’s handwriting perfectly. He “imitated the King’s handwriting so exactly,” wrote Saint-Simon, “that it cannot be distinguished from that which the pen counterfeits […]. It is not possible to make a great king speak with more dignity than Rose did, nor more appropriately to each person, nor on every subject, than the letters he wrote in this way, and which the King signed with his hand” (Saint-Simon, Mémoires, bibl. Pléiade, t. I, pp. 821-822).

11 000 €